listen magazine feature

Now eighty, a look back at the village vanguard's unlikely path

By Jed Distler

Changes come and go in Manhattan’s West Village neighborhood, but the basement club occupying 178 Seventh Avenue South since 1935 remains a stable and revered New York City landmark. It’s been tweaked for upkeep over the years, but never to the point where you wouldn’t recognize it.

You enter the Village Vanguard as you did when it first opened in April 1935, by walking fifteen steps down what might be described as a cross between a staircase and a chute. Then you find yourself in room shaped like a piece of pie. A small stage lives at the widest end. The room gets narrower as you move back. As you get close to the back, you’ll find the bar on one side. Tables and chairs occupy the center floor. The room officially seats one hundred twenty three people. Sightlines are good, except for the tables near big pillars.

Most importantly, the sound is good. You hear everything clearly from each corner of the room, whether it’s the big band presiding on Monday nights, a typical hard bop quintet or the more unusual guitar–viola–drums lineup of Bill Frisell’s Beautiful Dreamers. And the musicians can usually hear each other, which is important because of the intensely interactive nature of jazz. In a 2003 interview with Thomas Conrad, recording engineer Jim Anderson described the room as “big and quiet and fairly dead. When you put the mikes up, you forget that you are in this cave in the middle of New York. It’s sort of like a womb that you enter.”

“With minimal amplification in there, when you play very, very quietly, it has presence throughout the entire room,” says pianist Fred Hersch, a longtime regular on the club’s roster. “There’s a certain kind of stillness, a kind of hush, that you don’t get anywhere else.”

The sound was more than adequate for the poets, comedians, folk singers and public speakers who defined the club’s first twenty years, along in great part with its owner, Max Gordon. In his 1980 memoir Live at the Village Vanguard, Gordon described how he essentially fell into the nightclub business. Born in Vilna, Lithuania in 1903, Gordon grew up in Portland, Oregon, and graduated with a literature major from Reed College. He moved to New York City in 1926, not sure of what to do, but attracted to Greenwich Village’s Bohemian atmosphere and nightlife. He got to know all kinds of neighborhood characters and personalities, including a friend who suggested that if she and Max opened a place together, her poet friends would help attract a following.

The Village Fair lasted only three months, but Gordon’s following grew. Losing no momentum, he had designs on the Village Vanguard in February 1934. But to get a cabaret license, Gordon had to meet certain requirements. He found a former basement speakeasy called The Golden Triangle, “closed for alterations.” The place offered exactly what he needed: “two johns, two exits, two hundred feet away from a church or synagogue or school, and with rent under $100 a month.” By April 1935 the new Village Vanguard at 178 Seventh Avenue South was open for business, and still is.

In the club’s early, pre-liquor-license days, clientele ordered glasses, ice and soda and brought in their own booze. Each evening’s agenda was fairly loose, and mainly focused on poets, who’d read out loud and argue into the night about poetry, philosophy and politics. MC Eli Siegel moved the show along, kept hecklers at bay, and tried to maintain order over the chaos. A few years later, Max auditioned an untried teenage actress/singer named Judy Holliday, along with fellow aspirants Adolph Green, Betty Comden, John Frank and Alvin Hammer, who had been collaborating on “skits and songs of satire and social significance.” Max liked what he heard, and hired them on the spot. They named themselves The Revuers, and worked the Vanguard nearly every night. Sometimes a young music student named Leonard Bernstein helped out at the piano. Word got around, and a rave review by Dick Mason in the New York Post put both the Revuers and the Vanguard on the New York nightclub map. From then on, the Vanguard’s programming agenda came into focus.

In the forties and fifties, the Vanguard was more supper-club formal in its presentation, with white tablecloths, waiters in tuxedos and food served.

Although regular Monday-night jam sessions offered a broad range of jazz luminaries, it was folk singers, blues artists and entertainers who dominated the Vanguard bandstand during the 1940s. Fellow Village denizen and future film director Nicholas Ray recommended teaming up Josh White and Leadbelly for an act. White’s urbane and suave singing and playing style and Leadbelly’s rugged, elemental projection couldn’t have been more different, yet somehow they meshed. An avid young jazz fan and aspiring artist from Newark, New Jersey, Lorraine Stein, came to one of Leadbelly’s shows. A few years earlier, she and her brother tried to get in the Vanguard, but were too young to legally enter a bar. She told the Wall Street Journal’s Will Friedwald that the first words she ever heard uttered by Max Gordon, her future husband, were “Get rid of those kids!” Another early Vanguard performer, Burl Ives, recommended Richard Dyer-Bennet, the noted tenor who sang ancient Scottish, Irish and English ballads to his own lute accompaniment. Dyer-Bennet opened in 1942 and stayed at the Vanguard for the next three years, playing three shows a night, six nights a week. He would return off and on for another decade, and, in fact, served as best man at Max and Lorraine’s wedding.

Lorraine Gordon elaborated on the eclectic bill of fare characterizing the club’s early years in her 2005 memoir, Alive at the Village Vanguard. She remembered calypso acts who made good use of the little wooden dance floor, like Enid Mosier and the Trinidad Steel Band, and the Haitian actress and singer Josephine Premice, who later appeared on Broadway in Jamaica with Lena Horne and in the 1976 revue Bubbling Brown Sugar. The list of comedians who held forth at the Vanguard reads like a who’s who of stand-up comedy’s formative years, from longtime regular Phil Leeds, (who became better known as a film and television character actor), Wally Cox and Jack Gilford to several memorable early sixties runs with Lenny Bruce. One still can see Nat Hentoff’s 1963 interview with the controversial comedian; Bruce appears high and disheleved as he randomly pounds upon the Vanguard’s baby grand. Bruce’s mentor, Professor Irwin Corey, the “World’s Foremost Authority,” honed his unique absurdist brand of social commentary at the Vanguard, where he shared a bill with Pearl Bailey in the early forties.

In several respects, the Vanguard was a training ground for Max Gordon to break in new talent before booking them into the Blue Angel, the high-end supper club he opened with Herbert Jacoby in 1943 on New York’s then-fashionable Upper East Side. The club thrived for twenty years before closing in 1964. “Perhaps the most important thing about the Blue Angel, in retrospect, was the utter absence of racism on or off its little stage,” wrote Ms. Gordon. “Blue Angel audiences were always mixed audiences. New York nightlife, particularly in the upper echelons, was still shockingly segregated.” Max’s booking policies were just as colorblind as they were downtown. He brought the Irwin Corey/Pearl Bailey bill uptown, as well as Eartha Kitt, Harry Belafonte, Johnny Mathis, the Weavers and Mort Sahl. Conversely, Barbra Streisand triumphed at the Blue Angel, but a Vanguard gig eluded her until her special 2009 one-night-only appearance.

Yet while the Blue Angel flourished, the Village Vanguard more than held its own and remained Max’s favorite. In the forties and fifties, Ms. Gordon recalled, the Vanguard was more supper-club formal in its presentation, with white tablecloths, waiters in tuxedos and food served. But in May 1957, Max decided to “refresh the whole entertainment setup” and focus on modern jazz. At first he interspersed leading musicians of the day with verbal performers who had jazz followings, like Mort Sahl, Irwin Corey and, later, Lenny Bruce. Jack Keruoac, hot on the heels of his successful novel On the Road, took to the Vanguard stage, reading out loud to musical accompaniment. Soon after, purely musical programming followed.

Double bills were the rule rather then the exception. Bill Evans’ seminal 1961 trio performances retain their legend, but it’s sometimes forgotten that Evans shared the bill with the popular jazz vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross. One hears about John Coltrane’s uncompromisingly far-reaching 1966 Vanguard stint with his quintet post-A Love Supreme, but only a few remember the bill’s other “act,” an earlier tenor saxophone pioneer in his own right, Coleman Hawkins.

Despite the club’s single headliner policy, musicians invariably share the spotlight with shades of past and present legends. “The first time I played at the Vanguard I was nervous,” recalls pianist Christian Sands. “I was performing with the great bassist Christian McBride and his quintet Inside Straight. I remembered walking through the crowd, on the right side, trying not to knock over drinks on these small tables (it was so dark) and onto the small stage, bright lights hitting my face. I sat down at the piano thinking: ‘Herbie Hancock sat here. Miles Davis played right here, Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, Charles Mingus.’ The list went on and on. And suddenly our first tune started.’ ”

Max Gordon ran the club until he died in 1989. The following day, Lorraine Gordon assumed ownership and remains in charge, along with her daughter Deborah and long-time general manager Jed Eisenman. Under Ms. Gordon’s watch, the club has steadfastly maintained its integrity and high artistic standards while adapting a programming policy that is arguably more open and inclusive, though no less selective. “It goes back and forth between [honoring] the history of the music and what is going on now and where it should be going,” said Eisenman in an interview with pianist Ethan Iverson, who caught Ms. Gordon’s discerning ear and soon became a Vanguard favorite. Eisenman cites guitarist Bill Frisell as the person “more singularly responsible for still making the Vanguard look like it’s cool. He changed the landscape of my booking.” Frisell’s frequent collaborator, the late drummer, percussionist and composer Paul Motian, also played a crucial role in the Vanguard’s recent history.

“Paul was the driving force of the place for about ten years,” said Eisenman. “From 2001 to 2011, he was the artist-in-residence who not only worked there eight to ten weeks out of the year, but also helped me and Lorraine figure out how to go with the music and who to hire. He was a real part of the human fabric of the establishment. It was great to be able to foist that level of boldness and genius and cutting edge on people under the banner of Paul Motian, because we could get away with it.”

Yet while the music evolves, certain traditions remain, such as the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra, founded in 1966 by the late Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, still going strong on Monday nights. And while Ms. Gordon has open ears, she has a practical mind. “I encourage everyone who plays here to include at least one standard or ballad in every set — I say, ‘No one’s going out the door humming that original you wrote ten minutes ago.’ ”

Perhaps the most telling evidence that the Village Vanguard and jazz are as healthy as ever comes from those who reconnect with the club and the music after many years. Bassist Frank Canino, who first played the Vanguard in 1979 with tenor saxophonist Warne Marsh and pianist Sal Mosca, returned in 2010 to see Christian McBride’s quintet. “It was a life-altering experience,” said Frank. “That group, to me, brought back everything that I missed in jazz. Swinging to the point of being danceable like the old jazz bands, virtuoso playing at every position, every solo from each player was lyrical, told a story and found unexpected places to go yet never strayed too far from the blues. Everyone had a great sound; the dynamic range of the group as a whole was perfect. And there was an overall sense of humor involved with the entire performance. I couldn’t believe I was hearing something this good.”

Live at the Village Vanguard

5 Essentials

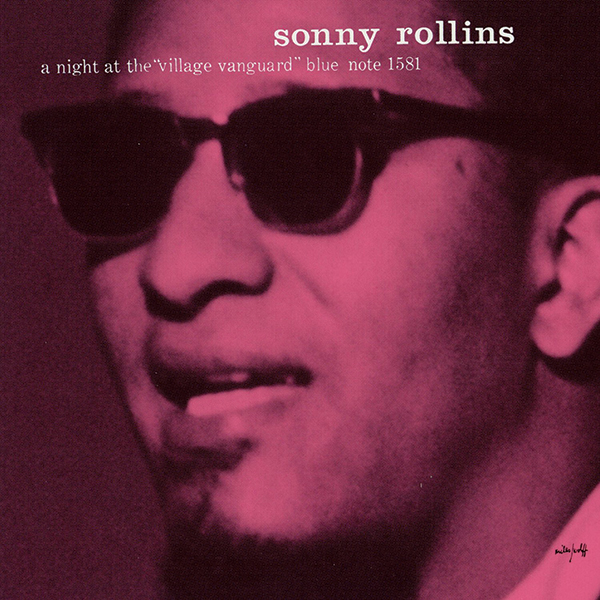

Sonny Rollins: A Night at the Village Vanguard (Blue Note), recorded November 3, 1957.

Sonny Rollins: A Night at the Village Vanguard (Blue Note), recorded November 3, 1957.

With just bass and drums behind him, the tenor saxophonist found the perfect canvas for his deceptively complex solos to flourish with a kind of controlled freedom that looked forward and back at the same time.

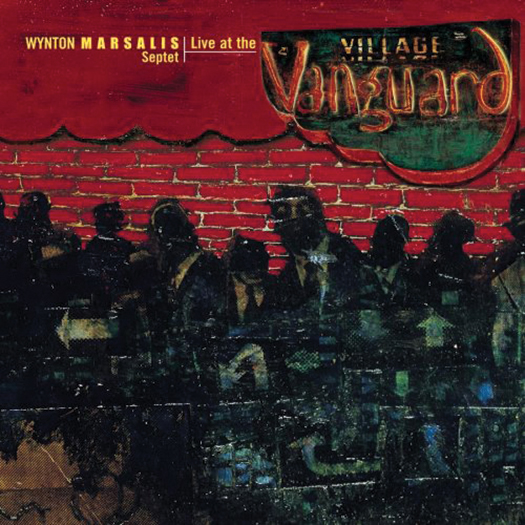

Wynton Marsalis Septet: Live at the Village Vanguard (Columbia Jazz), recorded 1991/4.

Wynton Marsalis Septet: Live at the Village Vanguard (Columbia Jazz), recorded 1991/4.

Mixing celebrated standards, catchy originals and ambitious extended works, this seven-disc set thoroughly vindicates Marsalis’ reputation as a summational force in jazz and as a bandleader who nurtures and showcases worthy emerging talent.

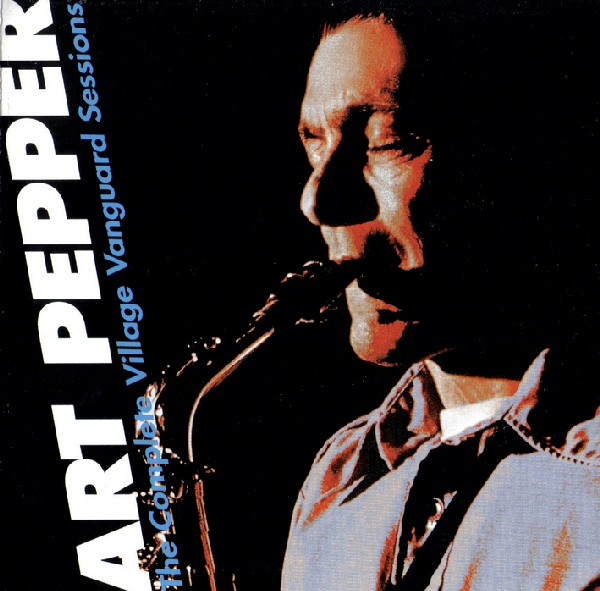

Art Pepper: The Complete Village Vanguard Sessions (Contemporary), recorded July 28–30, 1977.

Art Pepper: The Complete Village Vanguard Sessions (Contemporary), recorded July 28–30, 1977.

When the overwhelmingly talented and immensely troubled alto saxophonist returned to full time music making, the suave mastery of old gave way to raw-nerve, death-cheating virtuosity in every chorus, galvanized by a supportive yet combative rhythm section.

Paul Motian/Bill Frisell/Joe Lovano: You Took the Words Right Out of My Heart (Winter & Winter), recorded June 1995.

Paul Motian/Bill Frisell/Joe Lovano: You Took the Words Right Out of My Heart (Winter & Winter), recorded June 1995.

This intuitive, thoughtful, fluid and consistently inventive trio effortlessly interacts, yet knows what to leave unsaid.

Bill Evans: The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings 1961 (Riverside), recorded June 25, 1961.

Bill Evans: The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings 1961 (Riverside), recorded June 25, 1961.

The pianist, along with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, created a quiet revolution, elevating the archetypal jazz trio to an equal partnership. Their most finely honed interplay is gorgeously captured in recordings made during the trio’s last performance together, ten days before LaFaro’s untimely death in a road accident.

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.