Marion Anderson's historic Lincoln Memorial performance in 1937.

Listen Magazine FEATURE

Ten Great Classical Music Moments in America

By Kyle MacMillan

American classical music has witnessed great performances and memorable debuts, such as the 1944 premiere of Aaron Copland’s ballet Appalachian Spring, or seventeen-year-old pianist André Watts bursting into national prominence in 1963 with the New York Philharmonic as a substitute for soloist Glenn Gould. But some moments were magical enough to enrapture the public at large and become part of the fabric of the American cultural landscape. Here are ten of them.

1. Opening Of Carnegie Hall (May 5, 1891)

No venue is more closely associated with classical music in the United States than New York’s Carnegie Hall. Louise Carnegie ceremoniously laid the cornerstone for the one-million-dollar building in May 1890, and the Italian Renaissance structure opened with a five-day music festival. Among the highlights was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky conducting his “Marche Solennelle” and his First Piano Concerto. Scores of other landmark concerts and events have taken place within the legendary hall, including Igor Stravinsky’s 1925 American debut in which he conducted the New York Philharmonic, and bandleader Benny Goodman’s famous concert on January 16, 1938, a recording of which became one of the best-selling albums in jazz history (The Famous Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert (Columbia/Legacy)). In the late 1950s, with the impending development of Lincoln Center — which would become a new home for Carnegie Hall anchor tenant New York Philharmonic — the venue’s future was threatened. Famed violinist Isaac Stern led a campaign in 1960 to save the historic structure and it remains a pivotal American cultural force.

2. Tuesday Musical Concert Series (1892)

Classical music in the United States would never have prospered were it not for grassroots organizations that sprouted up across the country to present and promote it. Among the oldest of such groups is the Tuesday Musical Concert Series, formed in Omaha, Nebraska by four musically inclined women as a way to get together and perform in an informal setting. The group started interspersing professionals among its amateur members’ performances in 1903, and by 1915–16, the Series was solely presenting artists of national and international stature. And what a record of musical stars it can claim: Pablo Casals, Kirsten Flagstad, Jascha Heifetz, Vladimir Horowitz, Lotte Lehmann, Itzhak Perlman, Lily Pons, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Arthur Rubinstein, Artur Schnabel, Rudolf Serkin, Joan Sutherland and Isaac Stern. “Our aim has been all along to bring the very best artists that we could afford at the best prices that we could give to the Omaha audiences. It’s a very simple credo, and it has worked,” program co-chairwoman Eleanor Plumb told the Omaha World-Herald at the time of the group’s centennial. The Series has faced increasing competition and shrinking audiences in recent years and is on hiatus at the moment, but hopes to be back in action later this year.

A ticket stub Carnegie Hall’s opening night 1891.

Carnegie Hall in 1891

Van Cliburn returns to the stage triumphant after final round of the First International Tchaikovsky Competition, April 11, 1958, in Moscow

Original theatrical release poster for Fantasia

3. Dvorák In America (September 27, 1892)

Famed Czech composer Antonín Dvořák came to the United States to serve as director of the National Conservatory of Music of America in New York City for the then-princely salary of fifteen thousand dollars. During his time in this country, he composed some of his most beloved works, including his Symphony No. 9 (“New World”), which the New York Philharmonic debuted in 1893. He spent the summer of that year in the Czech–speaking town of Spillville, Iowa, where he wrote several pieces, including his “American” String Quartet in F Major, and visited several neighboring Midwestern communities. During his nearly three years in the U.S., he promoted the prescient and far-reaching idea of American composers looking to such indigenous musical sources as Native American chants and African-American spirituals for inspiration. “The new American school of music must strike its roots deeply into its own soil,” he wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Herald. “There is no longer any reason why young Americans who have talent should go to Europe for their education.”

4. Porgy and Bess (October 10, 1935)

It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that the history of American opera began with George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, which premiered in Boston on September 30, 1935, and opened ten days later at New York’s Alvin Theatre, running for one hundred twenty-four performances. Despite its confusing beginnings on Broadway — where it returned in 2012 in a controversial adaptation with a script by Susan-Lori Parks and direction by Diane Paulus — Porgy and Bess is very much an opera. Gershwin read DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy in 1922 and went on to collaborate with both Heyward and Ira Gershwin on the opera’s libretto. Although Gershwin did not incorporate actual spirituals into the work, he drew on their sound and spirit and injected a jazzy exuberance into his writing. The opera was subsequently revived in varying forms, including a 1952 European touring production that featured Leontyne Price as Bess, William Warfield as Porgy and Cab Calloway as Sportin’ Life. But the opera suffered from perceptions of racism, and it was not until a 1976 revival by the Houston Grand Opera, with its restoration of Gershwin’s complete original score, that Porgy and Bess was fully accepted as the great American opera that it is. The Metropolitan Opera staged its first production in 1985, solidifying the work’s place in the standard opera repertory.

5. Marion Anderson’s Lincoln Memorial Concert

(April 9, 1939)

Marian Anderson performed before seventy-five thousand people at the Lincoln Memorial in what has been called the first-ever public protest concert in America. Such a singular venue and mammoth crowd would have made this an important concert no matter what, but the circumstances surrounding it added to its gravity. Howard University in Washingon, D.C., wanted to present the singer in concert, but did not have a venue large enough. So, it tried to rent Constitution Hall but was rebuffed by the Daughters of the American Revolution because only whites were allowed to perform there. Outraged, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR and organized this outdoor concert with the memorial’s statue of Abraham Lincoln as the singer’s backdrop. Anderson began her concert with “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” and continued with Donizetti’s “La favorite” and Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” ending with three spirituals. “Miss Anderson had never considered herself to be an activist, but in fact, on that Sunday morning, she was,” wrote soprano Jessye Norman, who devoted a chapter to Anderson in her recent memoir, Stand Up Straight and Sing! (Houghton Mifflin). “When I think about how, despite the pervasive prejudice she experienced, she did not allow hatred to dampen the song within, I can only be grateful.”

She did not allow hatred to dampen the song within.

6. Fantasia (November 13, 1940)

With work nearing its conclusion on “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” a comeback vehicle for Mickey Mouse, Walt Disney decided to make the animated short part of a full-length film. Fantasia consisted of eight animated segments set to classical masterworks conducted by famed conductor Leopold Stokowski, including Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain. While many people might not know the names of the compositions featured, memories of them have been imprinted on successive generations of viewers who have enjoyed the bubble-blowing elephants, the maniacal brooms and a host of abstract effects. In 1998, the American Film Institute rated Fantasia as the fifth-greatest animated film ever, but just as important as its cinematic value is its unparalleled role in bringing classical music to thousands of children and adults alike.

7. Van Cliburn Wins The First International Tchaikovsky Competition (April 13, 1958)

In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite, ratcheting up Cold War tensions and setting off the Space Race. Less than a year later, a young pianist from Texas named Van Cliburn traveled to Moscow and managed to pull off a stunning upset, winning the first International Tchaikovsky Competition. Upon his return, he was treated like a conquering hero, earning a place on the cover of Time magazine and becoming the first and only classical music performer to enjoy a ticker-tape parade in New York City. Shortly thereafter, Cliburn joined Kirill Kondrashin, the conductor with whom he had played his prize-winning performances in Russia, for a trio of concerts in the United States. Their recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, made during that visit, became the first classical release to go platinum, ultimately selling more than three million copies. For decades, Cliburn was one of just a handful of leading classical musicians that nearly anybody — classical fan or not — could be counted on to know. He established the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Fort Worth in 1962, and it ranks among the most prestigious of such contests in the world.

“I understood that classical music could be highbrow but truly fun at the same time.”

— marin alsop

8. Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts

(January 18, 1958)

Just two weeks after becoming music director of the New York Philharmonic, conductor Leonard Bernstein led the first of his fifty-three Young People’s Concerts. Without being condescending or simplistic, Bernstein introduced children to classical music, paying tribute to such composers as Copland and Shostakovich and even taking on such challenging questions as “What does music mean?” — the topic of his first outing. Originally broadcast on Saturday mornings, the concerts were shown for three years during prime time on CBS and later shifted to Sunday afternoons. They brought classical music into American homes in a widespread and down-to-earth way that has never been matched on television nor anywhere else. Not only did these programs help develop devotees of classical music in general, but they also proved inspirational for a whole generation of youngsters who decided to make music their career. Among them was Marin Alsop, a native New Yorker who went on to study with Bernstein and become an internationally respected conductor. “I watched the Young People’s Concerts on CBS on Sunday afternoons,” she said, “but my father also took me in person, and it was at that first live concert that I knew that I wanted to become a conductor. Leonard Bernstein’s charismatic enthusiasm and passionate communicative style won me over immediately, and I understood that classical music could be highbrow but truly fun at the same time.”

9. Terry Riley’s In C (November 4, 1964)

After World War II, the American classical scene was dominated by atonal or serialist music, an academic approach that left little room for Romanticism and paid little heed to audience appeal. In the 1960s and ‘70s, a response to this musical dogma emerged: a tonally based musical style that came to be known as minimalism, with its iterative motives and slow harmonic progressions. Following the work of La Monte Young, minimalism came into its own with Terry Riley’s In C, which consisted of fifty-three interlocking phrases that can be played by any number or type of instrument. The work was premiered at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a reminder of the significant role that the West Coast has played in the evolution of American classical music. In C had a transformative impact on Steve Reich, who was one of the players at that first concert, and other major minimalist composers such as Philip Glass and John Adams, but its influence has traveled outside the genre as well, touching rock groups like The Who, The Soft Machine, Tangerine Dream and Curved Air.

10. The Forming Of Kronos Quartet (November 1973)

No American ensemble has had a more far-reaching impact on the development of contemporary classical music than the San Francisco–based Kronos Quartet, which made its debut at North Seattle Community College. It has commissioned more than eight hundred original works and arrangements — a staggering number by any measure — and has built ongoing relationships with composers such as Terry Riley, an association that yielded thirteen string quartets, a quintet and a concerto for string quartet. Violinist David Harrington founded the group after hearing a performance of George Crumb’s Vietnam-War–inspired Black Angels, with its haunting, perception-bending soundscape of bowed water glasses, electronic effects and shouts. Instead of performing the expected quartets by Beethoven or Debussy, Kronos Quartet gained fame by focusing on new, adventurous repertoire both inside and outside the classical realm. It has collaborated with such diverse musicians as pipa virtuosa Wu Mam, Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq, rock legend Paul McCartney and jazz vocalist Betty Carter, and has appeared on the recordings of such performers as Nine Inch Nails, DJ Spooky, Dave Matthews, Nelly Furtado and Joan Armatrading. In addition, noted choreographers like Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor and Eiko & Koma have created works using the quartet’s music. By successfully breaking from the conventional string-quartet model, Kronos Quartet has blazed the trail for the assortment of hybrid entrepreneurial groups that have popped up and energized the classical scene in recent years.

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.

related...

-

'But Beautiful'

A life with Billie Holiday

Read More

By Lara Downes -

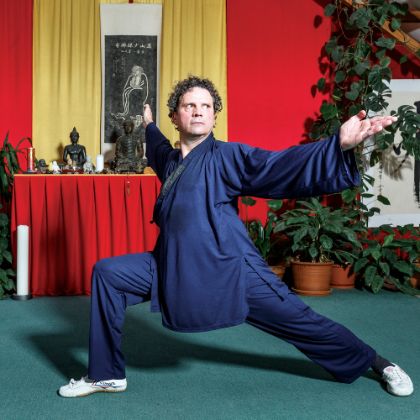

Kung Fu and the Art of Pianism

Andreas Haefliger finds a freer connection to the keyboard.

Read More

By Jens F. Laurson -

Conrad Tao: Leaving the Comfort Zone

Adventurous as a pianist and composer, Conrad Tao is reshaping the image of the piano virtuoso for the twenty-first century.

Read More

By Thomas May